|

Friday, August 6 -– Silver Trail I’ve hinted a couple of times about my previous gold panning experience. In 1969, when I was 19 years old, I took a summer job between 1st and 2nd year University with United Keno Hill Mines. The company was at one time the 4th largest silver producer in the world, the area around Keno Hill rich in silver. Although it operated for more than forty years until it shut down in the 1980s, it rarely had more than three years of known reserves. The search for the next ore body was a continuous effort. I was stationed in a little town called Elsa, the company’s headquarters, and worked at one of the mine sites in a town called Calumet. Diamond drilling rigs were sent out to get core samples so the company could evaluate where their mining efforts should next go. The rigs came in with 5-pound bags of dirt, each marked for which hole and for the depth that it came from, and dumped them all on a porch of a small building that I worked in with two other guys about my age. Two of us were panners and the other worked in the lab. Each day, we would first organize the bags of dirt in the right order. Each panner would have a large cast-iron sink, much like a laundry tub. In the bottom was a gold pan with a rectangular screened frame, similar to what you might use to sift dirt in your garden, sitting on top of it. I would take a bag of dirt and pour it into the screen, and wash the dirt with a hose until clean gravel was left. I had to write down the rough composition of the gravel; there were three kinds of rock that signified proximity to galena, an ore yielding silver and lead. Having done that, the gravel was discarded. I then panned what had washed through the screen until a small sample was left, enough to fill the bottom of one of those little papers that sit in the bottom of a muffin baking cup. The cup then went into the lab, where the composition of the sample in the bottom was examined under a microscope. I did this for sixteen weeks that summer. Along part of the Klondike Loop between Dawson City and Whitehorse lies the Silver Trail Highway. Starting at Stewart Crossing, the Silver Trail leads to Mayo, the city from which the S.S. Keno transported barges laden with silver ore down to Dawson City. When I worked up here in 1969, I remember one weekend very clearly. I was friends with one of the guys who had been working for a few years at the mine. He had native friends in Mayo and we were invited to stay overnight with their family, which consisted of a husband and wife, one of the grandparents and a number of children, from pre-school age to teenager. It was a two-room cabin with no running water. In summer, water was fetched by bucket from a stream. In winter, water was also fetched by bucket from the stream – after digging a hole in the ice to get it. The toilet was simply a chair a ways off from the cabin. You just moved the chair a bit if the need was apparent. Protected from the wind only by a 4’x8’ sheet of plywood, I can only imagine how comfortable it was to sit on that chair at 50 below in the wintertime. Saturday nights in Mayo were cause for special celebration. There were two licensed facilities – the upscale one was a hotel lounge for ladies and escorts, with Indians not allowed. The other facility was a bar in the Mayo Hotel for both Indians and whites, but usually no white women. My friend told me that there wasn’t any point getting there before 9pm. I thought it seemed a bit late, but as I was just along for the ride, went along with it. When we arrived, I found a small bar with about twenty round tables, each with four chairs, each chair occupied. These guys were serious drinkers, and had obviously been there awhile. There was only one drink – beer – and almost every table was stacked high with 3, 4, even 5 layers of empty beer cans. My friend said that we should just stay standing against the wall. Then, almost as if on cue, a fight broke out. As soon as the first punch was thrown, everybody at all the other tables stood up, picked up the tables, and moved them over against the walls. Then everybody got in on it. Imagine a barroom brawl in an old Western movie. That’s what it was like. There were bodies literally flying through the air and landing on the tables, sending the empties flying in every direction. And so long as you were standing against the wall, those in on the action seemed to recognize it as neutral ground. Live entertainment. The Silver Trail passes through Mayo on its way to Elsa and Keno Hill. We stopped at Mayo to try to find the hotel, but found that it had burnt down. Small wonder. When we arrived at Elsa, we were disappointed to find that although it was still a mining operation, it had changed hands and was not open to the public. The 25 or so remaining inhabitants of Keno Hill, on the other hand, welcome visitors. Among themselves, they have created the Keno Mining Museum. Its displays capture the mining history, and include tools and equipment from the bygone mining days, a collection of photographs, and artifacts associated with everyday life in the isolated mining communities. Looking through some of the photographs let me relive my time here. I also retraced the path I had taken 35 years ago to the 6,065 foot peak of Keno Hill, where the famous Signpost is. Above treeline, the panorama is breathtaking. The sign was originally erected in 1956, when the mining company hosted a group of visiting scientists. Arrows with mileages point to the cities all over the world represented by the delegates. For Silver Trail photos, click here. Saturday, August 7 -– Stewart Crossing to Whitehorse By staying at Stewart Crossing and just doing the Silver Trail as a day trip (our original itinerary had us staying the night in Keno City), we made up the extra day we spent at Denali National Park. So today, we’ll end up in Whitehorse. Good thing, too. The last few days, the boys have been anticipating seeing Sue and Larry in Whitehorse again. One of the stops we made was at Five Finger Rapids. Having had tours of the S.S. Klondike in Whitehorse and the S.S. Keno in Dawson City, we had seen pictures of these rapids. They were named by early miners for the 5 channels, or fingers, formed by giant rock pillars. They are a navigational hazard, and posed problems for the sternwheelers plying the river. The ships employed a technique called “lining”, in which cables, sometimes up to 15,000 feet in length, were towed ahead of the ship and fastened to a stationery point on the other side of the narrows. The cable was then taken in on the ship’s capstan, the ship literally winching itself through the rapids. Further along the way, we passed through the town of Carmacks, named for George Carmack, who established a trading post here in the 1890s. Carmack had come North in 1885, hoping to strike it rich. He spent the next 10 years prospecting without success. In 1896, when the trading post went bankrupt, Carmack moved North. His persistence paid off, as he and two others discovered gold. That same winter, he extracted more than a ton of gold from Bonanza Creek. When word of Carmack’s discovery reached the Outside the following spring, it set off the Klondike Gold Rush. Our last stop before Whitehorse was at Braeburn Lodge, one of the original roadhouses on the Overland Trail to Dawson. These roadhouses were about 20 miles apart from the next. Travelers could get a bed and meal, while pack horses or sled dogs could rest. Today, the lodge is an official checkpoint for the Yukon Quest Sled Dog Race, “The toughest sled dog race in the world.” More about that tomorrow. As well as being a checkpoint for the sled dog race, Braeburn Lodge’s other claim to fame is that it’s home to the most humongous cinnamon buns we’ve ever seen. One cinnamon bun is a feed for four people. However, the five of us stuffed down two of them. For Stewart Crossing to Whitehorse photos, click here. Sunday, August 8 -– Whitehorse This morning, we walked on the marge of Lake Leberge, made famous by poet Robert Service: “The Northern Lights have seen queer sights, but the queerest they ever did see, was that night on the marge of Lake Leberge I cremated Sam McGee.” David has been memorizing the poem since we left Dawson City. In the afternoon, we visited the Yukon Transportation Museum, which featured exhibits of all the forms of transportation used in the North. After spending the last couple of weeks immersing ourselves in the history of the Klondike, it was really neat to see it all in one place, from dog sleds to railways, from horse drawn sleighs to bush planes, from moosehide boats to sternwheelers, from the Chilkoot Trail to the Alaska Highway. Part of the Transportation Museum, which is located beside the airport, is an out-of-service DC-3 airplane that has been mounted on a pedestal to make a weathervane. It’s the most incredible thing to drive by a number of times, each time with the plane changing direction as it faces the wind. I mentioned yesterday that Braeburn Lodge was one of the checkpoints for The Yukon Quest, “The toughest sled dog race in the world.” It runs between Whitehorse, Yukon and Fairbanks, Alaska. Their brochure reads, “Teams must tackle white-out conditions in the mountains; fierce winds; temperatures dipping to -60 degrees Fahrenheit; four fearsome summits; icy slopes of glaciated streams; glare ice of the windswept Yukon River; unpredictable and problematic overflow [from still-frozen but melting streams]; steep windy side-hills; relentless switchbacks; natural moguls, and unexpected obstacles along the trail.” Sounds like fun, eh? The 10-14 day, 1,000-mile journey follows routes first used by fur traders, gold-seekers, missionaries, and mail carriers in the North. There’s debate among some people as to the relative challenges of the Iditarod and the Yukon Quest. Mushers who have gone in both say that there’s no question – the Yukon Quest is much more difficult. Rather than the 20-mile checkpoints of the Iditarod, those in the Yukon Quest are 40 miles apart. The only supplies you are allowed to carry are those you start with. You can’t replace dogs – if one gets sick or hurt, it drops out. And the terrain is much more challenging in the Yukon Quest, climbing over 4 mountain tops over 3,500 feet high. Just outside of Fairbanks at 434 feet elevation is one of those summits, a grueling start or finish as the start of the race alternates each year between Fairbanks and Whitehorse. The CBC did an excellent one-hour documentary of last year’s race (we bought a DVD of it) that really gives a sense of just how difficult the race is. Next door was the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre. Using multi-media, films, dioramas, and artifacts, it traces the Ice Age in Alaska and Yukon, which unlike the rest of Canada, was ice-free. The huge Cordilleran, Laurentide and Siberian ice sheets, up to 4km in depth, absorbed so much of the world’s water that the water level in surrounding oceans dropped 100 meters. Unlike the mythical Atlantis, a sub-continent was exposed. Known as Beringia (pronounced brr-in’-jee-uh, derived from the Bering Sea) it included a land bridge between Asia and North America. The earliest remains of humans in the New World is from this region. Numerous placer mining operations in the North have unearthed remains of wooly mammoths, giant bears, sloths, scimitar cats, and lions, providing evidence of the veracity of First Nation legends of ancestors attacking, or being attacked by, huge animals. One of the hands-on exhibits demonstrated the use of the atlatl, a handle that extends the length of the human arm, giving it much more power to propel a spear. The boys loved this one, throwing spears at plywood mammoths and giant bears. For more Whitehorse photos, click here. |

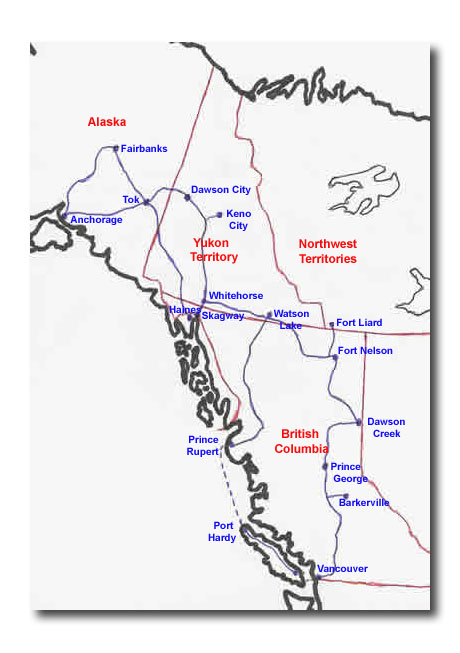

Dawson City to Whitehorse

Scroll down to read our Journal on Dawson City to Whitehorse.

For Silver Trail photos, click here.

For Stewart Crossing to Whitehorse photos, click here.

For more Whitehorse photos, click here.